***

There are a final few weeks to experience this stunning exhibition, currently showing at the Getty Centre until mid September. Entitled The Spectacular Art of Jean-Leon Gerome,this breathtaking collection of fine paintings and sculpture by this much-maligned mid-19th Century French artist is truly magnificent and is not to be missed.

Commercially successful, outspoken and controversial, Jean-Leon Gerome was a prolific artist whose talent was impossible to ignore. A painter and engraver, and then later in life a sculptor, he worked predominantly in the figurative style now known as Academicism. Cleaving to this classical style when many of his contemporaries were on the vanguard of an exciting new direction in Art (Impressionism), the range of Jean-Leon Gerome‘s oeuvre included historical painting, Greek mythology, Orientalism, portraiture and other subjects.

Gerome was among the most officially honored and financially successful French artists of the second half of the 19th century. His brilliantly painted and often provocative pictures were at the center of heated debates over the present and future of the great French painting tradition.

The J. Paul Getty Museum is the first of three venues to present The Spectacular Art of Jean-Leon Gerome. This much-anticipated special exhibition, running until September 12th, 2010, is the first of its kind in nearly forty years, and features a staggering 99 works by the French artist (1824-1904) as well as selected works by important contemporaries.

In light of recent scholarship, the comprehensive exhibition reconsiders the life and oeuvre of the academic painter and sculptor whose brilliant career was eclipsed by the development of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and the Modernist avant-garde.

ABOUT THE ARTIST:

Jean-Leon Gerome was born at Haute-Saône Vesoul on May 11th, 1824. (He died January 10th, 1904.) In 1840 Gérôme traveled to Paris where he studied in Paris under the tutelage of the academic painter Paul Delaroche. The pair travelled together to Italy during 1843-1844, visiting Florence, Rome and the Vatican as well as Pompeii.

Once he had returned to Paris, Gerome followed the path of several other pupils of Delaroche and went to the atelier of Swiss artist Charles Gleyre where he trained for a short period.

He next enrolled in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. During 1846 he attempted to participate the esteemed Prix de Rome, although was unsuccessful in the last phase as a result of his figure drawing being deemed ‘insufficient.’

A French government prize, the Prix de Rome was a scholarship for arts students, principally of painting, sculpture and architecture. It was created, initially for painters and sculptors, in 1663 in France during the reign of Louis XIV. It was an annual bursary for promising artists who proved their talents by completing a very difficult elimination contest.

Edouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Ernest Chausson and Maurice Ravel attempted the Prix de Rome, but did not gain recognition. Jacques-Louis David, having failed three years in a row, considered suicide.

The heyday of the Prix de Rome was during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Jean-Leon Gerome attempted to improve on his technical skills by painting Young Greeks Attending a Cock Fight, also called The Cockfight (now owned by the Musee Orsay, Paris).

The Cockfight (1846) was an academic exercise depicting a nude young man and a lightly clothed young woman observing two fighting cocks with a backdrop the Bay of Naples.

Jean-Leon Gerome commenced work on this canvas in 1846 when he was still bruised from his failure to win the Prix de Rome, which would have opened the doors of the Villa Medicis to him. Feared further rejection, he hesitated to present his Young Greeks Attending a Cock Fight for exhibit. Encouraged by his master, Delaroche, he finally entered his painting in the Salon of 1847, where it was a great success, gaining him a third-class medal. The novelty and appeal of such an accessible genre piece provided Jean-Leon Gerome entree into the Art world, epitomizing the so-called “neo-grec” movement.

The Salon was the name given to the official – and for many years the sole – exhibition for artists”™ work in Paris. It was established and organized by the Académie Royale and was held in the Louvre in the Salon Carré, from which it derived its name. Critical acclaim received at the Salon was of the highest importance for the advancement of a painter’s career.

The picture received great acclaim because he used a refined, classicist manner to depict a witty, light-hearted scene about adolescent sexuality on the grand scale of serious history painting.

Employing the Neo-Grec style, characterized by a taste for meticulous finish, pale colors and smooth brushwork, here Jean-Leon Gerome portrays a pair of scantily-clad adolescents at the foot of a fountain in an idyllic classical landscape. Their youthfulness contrasts with the battered profile of the Sphinx in the background. The same opposition is found between the luxuriant vegetation and the dead branches on the ground, and in the fight between the two roosters, one of which is doomed to die.

In the chorus of praise for the work, barely anyone but Baudelaire criticized the canvas, calling Gerome the leader of the “meticulous school”, and deeming him weak and artificial.

The public, however, preferred the opinion of novelist and critic Theophile Gautier who saw in The Cockfight “wonders of drawing, action and color.”

At the age of twenty-three, Jean-Leon Gerome had made a brilliant entry into the art world. He abandoned his dream of winning the Prix de Rome and took advantage of his sudden success, thereafter pursuing the official career he had planned for himself, punctuated with honors and rewards. Subsequently, the State commissioned numerous works from him.

Eventually awarded the Legion of Honor, Jean-Leon Gerome became a leading professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, specializing in the neo-Greek and historical subjects. An exhibitor at the Salon, Gerome epitomized the late 19th-century Paris Art establishment.

His works were wildly popular with the rapidly expanding bourgeoisie, eager to pay outrageous suns of money for his meticulously crafted paintings capturing the evocative history of ancient Greece and Rome. Capitalizing on his popularity, he fueled his commercial success and supplied enthusiastic buyers with an endless supply of photographic and engraved reproductions of his most famous works.

Reproduced using brand new photo-mechanical processes and dispersed across Europe and America, Jean-Leon Gerome‘s images indelibly marked the popular imagination, directly influencing spectacular forms of mass entertainment, from theater to film.

Critics lambasted him for this, as well as his imperfect drawing skills, laborious compositions and pedestrian brushwork. Jean-Leon Gerome‘s increasing fame sat at odds with a new shift the course of French art, led by contemporaries such as Edouard Manet and fellow Impressionists who were radically changing the face of the art world. The Impressionists broke the rules of academic painting by giving colors, freely brushed, dominance over line and form. Jean-Leon Gerome vilified the Impressionists, calling them “barbarians” and they loathed him in return. Jean-Leon Gerome was considered their ‘Anti-Christ’.

Despite his proclivities as a genre painter, Jean-Leon Geromealso manifested serious ambitions as a history painter, as history painting remained the highest genre in the theoretical hierarchy authorized by the French Academy and inculcated by the École des Beaux-Arts. He announced these ambitions at the 1855 Universal Exposition in Paris, where he exhibited a huge allegorical composition entitled The Age of Augustus (1855; Musee d’ Amiens), an official government commission which sought to flatter Emperor Napoleon III. Monumentally ambitious in size and conception, The Age of Augustus was nevertheless a critical failure, and Jean-Leon Gerome would subsequently turn his attentions to the far more lucrative arena of small-scale historical and Orientalist genre painting.

By the late 1850s, Gerome proved incredibly shrewd in choosing popular historical subjects ranging widely from ancient Greece and Rome to modern-day France and staging them in an instantly memorable fashion. He imbued historical scenes with a heightened degree of realism that reflected the scientific, positivist ethos of the period with its emphasis on visual observation and tangible facts. He refused poetic generalizations and idealizations when rendering his protagonists. Rather, he faithfully executed archaeological details and devised new compositional strategies that helped create a dramatic sense of eyewitness immediacy.

Photographic realism – The Death of Caesar

Julius Caesar was assassinated in Rome on the Ides of March (March 15), 44 BC. Characteristically, Jean-Leon Gerome has depicted not the incident itself, but its immediate aftermath. In The Death of Caesar (1867, the Walters Art Museum) Jean-Leon Gerome went to great lengths to meticulously reconstruct the archaeological details of the Roman Senate, offering the viewer a commanding panoramic overview in its portrayal of the dramatic events that unfolded following the ruler”™s cold and calculated assassination.

With cool, photographic detachment, he focused on the inglorious aftermath of Caesar’s assassination the unceremoniously abandoned corpse, the overturned throne and blood-spattered statue in the foreground, as well as the exultant group of Senators exiting the hall in the remote background. The charged void between them, accentuated by the vastness of the surrounding architectural space, imbues the solemn scene with tremendous dramatic power.

The illusion of reality that Jean-Leon Gerome imparted to his paintings with his smooth, polished technique led one critic to comment, “If photography had existed in Caesar’s day, one could believe that the picture was painted from a photograph taken on the spot at the very moment of the catastrophe.”

Christian Martyrs:

William T. Walters commissioned this painting in 1863, but the artist did not deliver it until twenty years later. In a letter to Walters, Jean-Leon Gerome identified the setting as ancient Rome’s racecourse, the Circus Maximus. He noted such details as the goal posts and the chariot tracks in the dirt.

Playing fast and loose with the facts, however, the seating, however, more closely resembles that of the Colosseum, Rome’s amphitheater, in which gladiatorial combats and other spectacles were held. Similarly, the hill in the background surmounted by a colossal statue and a temple is nearer in appearance to the Athenian Acropolis than it is to Rome’s Palatine Hill.

The artist also commented on the religious fortitude of the victims who were about to suffer martyrdom either by being devoured by the wild beasts or by being smeared with pitch and set ablaze, which also never took place in the Circus Maximus. In this instance, Jean-Leon Gerome, whose paintings were usually admired for their sense of reality, has subordinated historical accuracy to drama.

ORIENTALISM:

Jean-Leon Gerome‘s interest evolved from Neoclassicism to the exotic and Romantic Orientalist subjects that were the fashion of the day. Hetraveled widely and frequently in North Africa and the Near East, recording the terrain, customs and fashions that he witnessed, and becoming a diligent student of the history and culture of the exotic Near East.

Like many of his contemporaries, such as Delacroix, Gerome was lured by the romanticism of exotic lands. In 1856 he visited Egypt for the first time and the Near East. He produced a series of Oriental genres and figure studies that heralded the start of many Orientalist paintings depicting Arab religion, genre scenes and North African landscapes.

Interior of a Mosque:

Jean-Leon Gerome was the most popular and influential French academic painter of the second half of the 19th century and a leader among artists specializing in Oriental subjects.  During trips to North Africa and the Near East he made countless drawings, which he transformed into paintings, such as this one, in his Paris studio. The documentary quality of this masterful work is achieved by Jean-Leon Gerome‘s meticulous technique, by his ability to suggest subtle nuances of light and atmosphere, and by his precise evocation of the worshippers in all stages of their devotion, from the initial upright recitation of vows to the final prostration before God.

Snake Charmer

The Snake Charmer focuses on a naked boy handling a python while an old man plays a fipple flute. Watching intently is a group of mercenaries differentiated by the distinctive costumes of their tribes, by ornaments and by their weapons. Such erotic and exotic imagery of Near Eastern subjects was extremely popular in the late nineteenth century. Despite the nearly photographic realism employed by Jean-Leon Gerome, the painting is a pastiche of Egyptian, Turkish, and Indian elements that has little basis in reality.

The inventive imagery of Jean-Leon Gerome‘s subsequent The Snake Charmer (ca. 1870) was due, in part, to his 1853 trip to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey). There he derived inspiration from everyday life in the East to paint exotic scenes with the realistic clarity of photography, a new medium he greatly admired.

Linda Nochlin publishes her essay “The Imaginary Orient” in Art in America, describing how “the insistent, sexually charged mystery at the center of this painting” in the form of the charmer’s naked body suggests the “mystery of the East itself.” Even the image of the decaying building is loaded, she writes, with stereotypes of “Eastern idleness and neglect.”

After being shown in this current Getty exhibition, the painting will be a centerpiece of the Jean-Leon Gerome show at the Musee d’Orsay in Paris in October. Apparently this marks the first time the work will be in France since it was painted.

TRANSITION TO SCULPTURE:

Thanks to his enduring interest in antique art, Jean-Leon Gerome devoted much of his later career to sculpture, even frequently cross-referencing his own paintings and statues. Jean-Leon Gerome‘s first bronze sculpture, a gladiator trampling upon his victim, was premiered at the Universal Exposition of 1878.

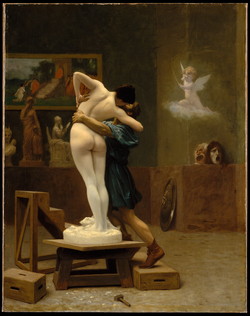

This current exhibition displays ten of Jean-Leon Gerome‘s works in bronze, marble, ivory and mixed media. It also fittingly includes the painter’s famous oil on canvas Pygmalion and Galatea (1890), in which he captures the ancient and enduring Roman myth of a sculptor who fell in love with his own creation brought to life by a goddess. This myth also inspired George Bernard Shaw’s famous play Pygmalion, which, in turn, was the basis for the musical My Fair Lady.

EXHIBITION LAYOUT:

In Los Angeles, California, the installation is brilliantly organized both thematically and chronologically by Mary Morton, Curator and Head of the Department of French Paintings at the National Gallery of Art and Scott Allen, the Getty”™s Assistant Curator of Paintings. Bravissimi!

Organized in collaboration with the Musee d’Orsay in Paris, and assembling 99 works from galleries across the globe, including:

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Art Institute of Chicago; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco; National Gallery, London and the Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

The Getty Museum has created a stunning exhibition. The Spectacular Art of Jean-Leon Gerome runs until September 12th, 2010 here in LA before it travels to the Musee d’Orsay in Paris and then the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid.

The Spectacular Art of Jean-Leon Gerome

The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center

1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles

Open:

Tuesday-Friday 10:00 a.m.-5:30 p.m.

Saturday 10:00 a.m.-9:00 p.m.

Sunday 10:00 a.m.-5:30 p.m.

Monday CLOSED

Closed Mondays and on January 1, July 4 (Independence Day), Thanksgiving, and December 25 (Christmas Day).

Admission to the Getty Center and to all exhibitions is FREE””no tickets or reservations are required for general admission.

Public Transportation

Get to the Getty Center via public transport! The Getty Center is served by Metro Rapid Line 761, which stops at the main gate on Sepulveda Boulevard. To find the route that is best for you, call (800) COMMUTE or use the Trip Planner — the Web site of the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Parking is $15 per car. Entry is FREE after 5:00 p.m. for the Getty Center’s evening hours on Saturdays (when they are open until 9:00 p.m.), as well as for all evening public programming, including music, film, lectures, and other special programs held after 5:00 p.m.

Parking reservations are neither required nor accepted. For more parking information, see hours, directions, parking.

and frequently asked questions.

Review by Pauline Adamek

Lovely article dude, appreciate it.