Regarding the depiction of real estate developers in film and on TV, it’s common to see the developer presented as the antagonist — the villain. Why is this common trope so enduring?

Here’s why:

In storytelling, conflict always provides good dramatic possibilities. The appearance of an antagonist, such as a real estate developer, can create a type of conflict wherein a new structure or presence threatens a heretofore close-knit community, threatening its way of life or its very existence.

This leads to the ‘David and Goliath’ trope of the small band of scrappy rebels fighting a greater, seemingly insurmountable oppressive force and – for a happy resolution – prevailing. E.g. Star Wars.

Of course, if the story is a tragedy, then they fail.

In other words, in the more optimistic invocations of the trope, the citizens band together to defeat the new development. In the less optimistic, we learn that progress is unstoppable.

The immutable fact remains that real estate developers are primarily motivated by financial gain rather than by the improving of lives of others, especially given that there are generally costs, losses or sacrifices forcibly imposed on the recipients – aka victims – of the development.

The trope of developer as a villain rather than benevolent altruist taps into the history of Colonialism and Imperialism, where oppressors have destroyed regions expressly for financial gain. (Colonialism is the policy of a country seeking to extend or retain its authority over other people or territories,generally with the aim of economic dominance. Similarly, Imperialism is a policy or ideology of extending a country’s rule over foreign nations, often by military force or by gaining political and economic control of other areas.)

Additionally, a ‘carpetbagger’ was a derogatory term applied by former Confederates to any person from the Northern United States who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War; they were perceived as exploiting the local populace.

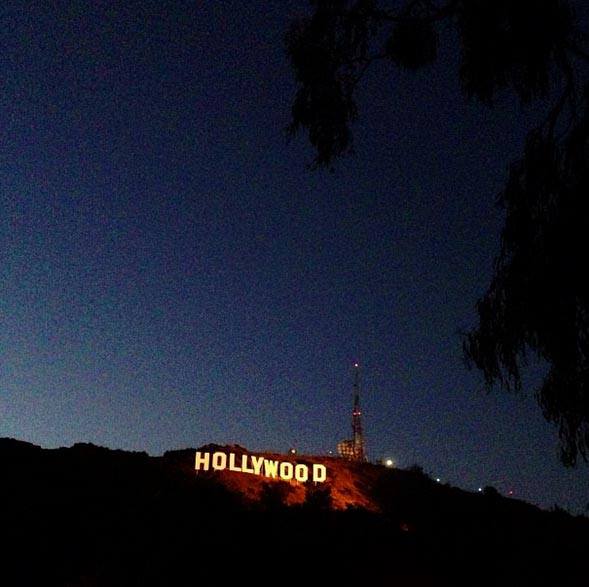

The developer-as-villain has a long and renowned history in popular Hollywood films. (Naturally, it existed before movies — in stage plays and in novels.)

Director Frank Capra was instrumental in establishing the trope, having employed it twice: in You Can’t Take it With You (1938), which hinges on a rapacious businessman’s efforts to snatch a home from a reluctant seller, and most famously in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). In the latter film, a smaller, demonstrably less greedy developer George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart – heroic protagonist) stands up to slumlord Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore – evil antagonist), the richest man in Bedford Falls. In the process, our hero sacrifices his dreams to ensure the survival of the savings and loan that he inherited from his father.

Other U.S. film examples include:

- A character is called out as a real estate developer to show the audience that he is unsavory (see Beetlejuice, Caddyshack, Summer Rental).

- A beloved building/piece of land/town will be destroyed by an evil developer if the heroes can’t come up with a large amount of money. (The Goonies is the purest example of this genre, but many others, such as The Brady Bunch Movie, follow a similar formula).

- The evil developer has a plot to increase the value of an investment, which needs to be stopped by the heroes. (Lex Luthor is the plotter in Superman.)

The evil developer movie boomed in popularity during the 1980s. This was the era of the yuppie, when factories closed and real estate moguls prospered. It was also a time of real-life economic swings, from the high inflation and interest rates of the early 1980s—followed by a recession—to the Savings and Loan Crisis of the last part of the decade.