An ancient legend first popularized in sixteenth-century Germany, the Faustian bargain warns of trading one’s soul or moral integrity for power, beauty, or success, only to pay a terrible price later. It remains one of the most enduring ideas in Western imagination because it captures the tension between ambition and restraint, between what we desire and what it costs to achieve it. The story emerged from German folk tales about scholars and magicians who made pacts with the devil, and in nearly every version the bargainer’s triumph turns to ruin.

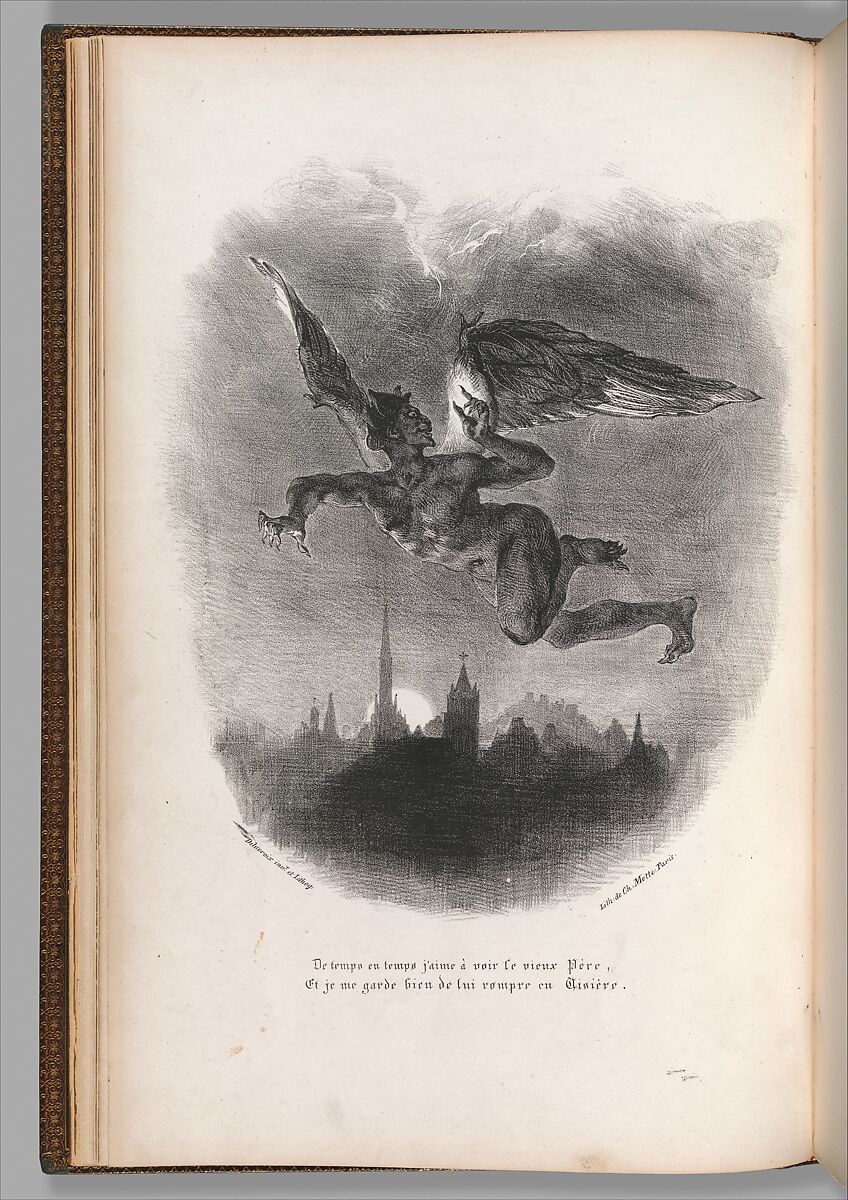

Image: Faust by Eugène Delacroix (French, Charenton-Saint-Maurice 1798–1863 Paris) 1828, Lithograph. Public domain.

From Doctor Faustus to The Picture of Dorian Gray, and more recently films such as Justin Tipping’s Him, artists have returned to the Faustian motif to explore obsession, temptation, and the human appetite for transcendence. The legend’s shape is endlessly adaptable, capable of reflecting each era’s anxieties about knowledge, beauty, and moral compromise.

Recent works like Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance and Max Minghella’s Shell reimagine the myth for the age of influencer capitalism and self-optimization. In these stories, the devil’s contract becomes a wellness treatment or subscription service, and the soul is exchanged not for forbidden knowledge but for beauty, relevance, and immortality. Both films are modern parables of vanity and self-improvement, where women face a cruel choice: fade quietly from view, or sacrifice themselves for the illusion of perpetual youth. The result is a sleek, unsettling reworking of the old Faustian bargain—proof that the desire to transcend one’s limits, and the fear of what that desire might cost, remain as powerful as ever.

Major incarnations of the Faust legend:

1480–1540 — Historical Johann (Georg) Faust

A wandering German scholar, astrologer, and alchemist. Contemporary accounts accused him of arrogance and dealings with the devil. After his mysterious death around 1540, stories circulated that he had sold his soul for knowledge and power.

1587 — Historia von D. Johann Fausten (The Faust Book)

Anonymous German chapbook published in Frankfurt.

This is the first printed version of the Faust story. It presents Faust as a learned man who makes a pact with the devil for 24 years of knowledge and pleasure, only to be dragged to hell. Written as a Protestant moral warning against pride and sorcery.

1592 — The History of the Damnable Life and Deserved Death of Doctor John Faustus

English translation of the 1587 Faustbuch. This version became popular in England and directly inspired Marlowe’s play.

1592 (published 1604) — Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus

The first great dramatic treatment of the story.

Marlowe transforms Faust into a Renaissance intellectual whose ambition to know and master all things leads to his damnation. Mephistopheles becomes a complex, tragic figure. The play ends with Faust’s soul seized by devils — a stark moral and existential tragedy.

1725 — New Faustbuch Editions and Puppet Theatre Versions

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the Faust legend spreads in popular culture through cheap print editions and traveling puppet plays. These versions emphasize comic and spectacular elements — magic tricks, demons, and slapstick — and help keep the legend alive in popular memory.

1772–1775 — Goethe’s Early Urfaust

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe begins writing his own version of the story. His Urfaust draft focuses on Faust’s relationship with Gretchen (Margarete) and the psychological consequences of his desires. It marks a shift from moral condemnation to philosophical and emotional depth.

1808 — Goethe’s Faust, Part I

Published as a complete drama. The work combines tragedy, theology, and metaphysical reflection. Faust’s dissatisfaction with human knowledge leads him to bargain with Mephistopheles. The Gretchen tragedy becomes the emotional center. Unlike earlier versions, Goethe allows for the possibility of redemption through striving and love.

1832 (published posthumously) — Goethe’s Faust, Part II

Expands the story into a cosmic allegory encompassing art, politics, science, and salvation. Faust seeks meaning through worldly and creative endeavors. At the end, he is redeemed — his striving spirit saved by divine grace. This work completes the transformation of Faust from sinner to symbol of human aspiration.

1829 — Louis Spohr, Faust (Opera)

The first major operatic adaptation. Spohr’s work, based loosely on Goethe, presents Faust as a man redeemed through repentance. It established a Romantic musical tone for later composers.

1846 — Hector Berlioz, La Damnation de Faust

A “dramatic legend” rather than a traditional opera. Inspired by Goethe’s Faust Part I.

Combines narrative scenes with orchestral and choral tableaux. Faust is ultimately damned and dragged to hell, while Marguerite is saved. Notable sections include the “Hungarian March” and Marguerite’s aria “D’amour l’ardente flamme.”

1859 — Charles Gounod, Faust (Opera)

Based mainly on Goethe’s Part I.

Centers on the love story between Faust and Marguerite. Gounod’s version became one of the most frequently performed operas of the 19th century. The work ends with Marguerite’s salvation and a heavenly chorus, combining moral redemption with Romantic lyricism.

1868 — Arrigo Boito, Mefistofele (Opera)

Italian adaptation that draws on both parts of Goethe’s Faust.

Boito’s opera is grand in scale and philosophical in tone, beginning with a “Prologue in Heaven” and ending with Faust’s salvation. Its music ranges from infernal choruses to mystical climaxes. Boito’s Mefistofele is sardonic, echoing Goethe’s Mephistopheles closely.

Mid-19th century — Franz Liszt, Faust Symphony (1854–1857)

A symphonic work in three movements representing Faust, Gretchen, and Mephistopheles.

Liszt translates Goethe’s psychological and moral themes into purely instrumental form.

20th century and beyond

Modern reinterpretations include Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus (1947), which links the legend to Germany’s cultural and moral collapse in the 20th century; F. W. Murnau’s silent film Faust (1926); and numerous theatrical, cinematic, and musical adaptations that continue to explore the idea of the “Faustian bargain.”

| Year | Title | Author/Composer | Medium | Outcome of Faust |

| c.1540 | Life of Johann Faust | Historical figure | Folklore | Dies mysteriously |

| 1587 | Historia von D. Johann Fausten | Anonymous | Prose | Damned |

| 1592 | Doctor Faustus | Christopher Marlowe | Play | Damned |

| 1808/

1832 |

Faust Parts I & II | Goethe | Drama/Poetry | Redeemed |

| 1829 | Faust | Louis Spohr | Opera | Redeemed |

| 1846 | La Damnation de Faust | Hector Berlioz | Dramatic legend | Damned |

| 1859 | Faust | Charles Gounod | Opera | Marguerite saved |

| 1868 | Mefistofele | Arrigo Boito | Opera | Redeemed |

[…] for Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn came with hilariously grisly side effects. All three movies update the Faustian bargain legend for the age of influencer capitalism and self-optimization, turning the devil’s contract into […]