Traditionally, the power of theater derives from it being a communal art form – a group gathers in person for a performance that is live and ephemeral. It’s the sense that the combination of that particular audience and those particular performers has created something special, a moment of art that can never exactly be repeated, which gives theater its aesthetic cachet; the insider privilege of being in “the room where it happened,” so to speak. But during this pandemic, the room where it happens has had a bar put over the door, and artists who want to continue doing theater have to do so via the medium of streaming video. This is a challenge to all of theater’s strengths – it’s not a physical gathering of people in the moment. But theater, that fabulous invalid, is nothing if not adaptable, and excellent productions such as Jake Broder’s new play, UnRavelled, show that theater artists are up to the challenge.

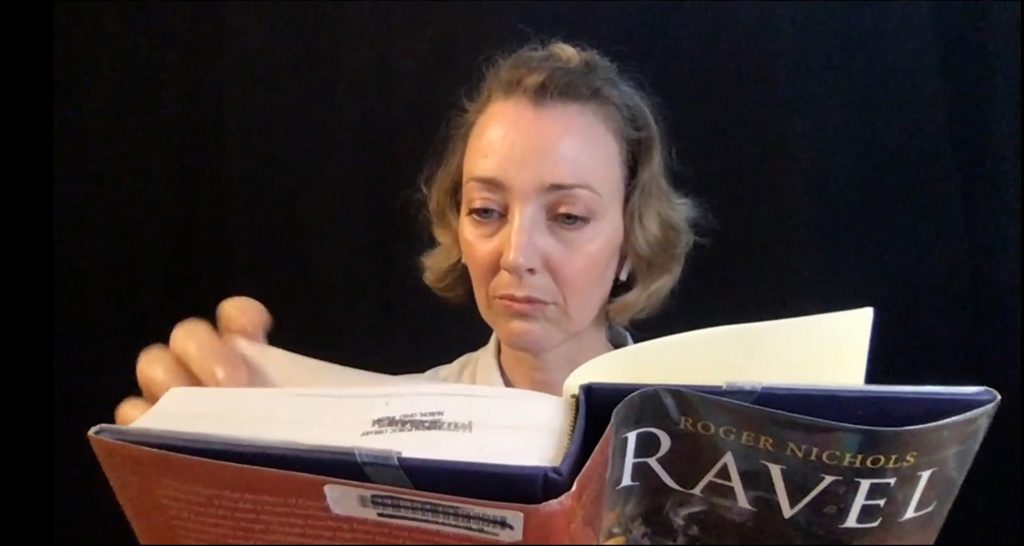

Broder’s play is based on the true experiences of Anne Adams (Lucy Davenport) and Robert Adams (Rob Nagle), a married couple whose lives took a turn for the tragic yet fascinating. Anne, a scientist, had taken time off from her career to care for their son after he’d experienced a serious accident. She uses this time to take up fine arts. After her son’s health has improved, she surprises Robert with the announcement that she wants to concentrate on painting instead of returning to science. Fixated on composer Maurice Ravel’s (Conor Duffy) Boléro, she creates a visual representation of the famous orchestral piece.

While Robert and others are impressed by her obvious yet sudden artistic flowering, demonstrated by works that translate the numerical concept of pi or the feeling of a migraine into an artwork, not all of her developments are positive. Robert notices that she’s struggling with words and suffering terrible headaches. Dr. Bruce Miller (Leo Marks) informs them that Anne has frontotemporal dementia, a degenerative condition shared by Ravel, which will eventually rob her of language, understanding and her life. Through their work together, however, they discover that while parts of her brain are failing, the other parts of the brain dealing with artistic creativity are surging with activity.

Davenport gives a superb performance as Anne, completely believable as an intelligent woman placed in a curious situation in which a dire mental ailment is combined with an explosion of artistic talent. She walks a fine line as the character, alternating moments of frustration about feeling that’s she’s being “studied,” anger or abrupt personality shifts with growing instances of artistic expression and obsession. She’s terrific in the role, and the emotional power of the show can be distilled in the difference between Anne’s early, lively self and the staring, silent Anne who faces us at the end.

Nagle is sympathetic and moving as Robert, who can only watch as Anne is inexorably pulled away from him. He does a strong job of showing the difficulties of being the partner responsible for the care of a loved one with a serious degenerative condition, of continuing to love someone when you can’t tell if they’re even “there” anymore. Marks brings warmth and wit to his portrayal of Dr. Miller, doing a lot of the expository scientific explanation of the piece with seemingly effortless style, especially in an anecdote where he explains the appeal of modern art – “I love it, but I don’t know why.” Duffy skillfully contrasts a bracing honesty (“You have no fucking idea what it’s like to know that there is something coming that is going to eat you alive.”) with confused vulnerability as Ravel. Melissa Greenspan excels in two roles, especially as Ravel’s patron, Ida Rubenstein, who affectingly describes how the word “unseemly” nearly ruined her life.

Broder’s writing is erudite, emotional and often genuinely funny, striking a balance between the personal and the philosophical. He crafts a play in which explaining how Picasso’s genius was translating time into a visual form and a re-creation of Bo Derek’s slow-motion run down the beach in the seventies film 10 can comfortably coexist. He presents the scientific inquiries and discoveries of the story in a compelling way, demonstrating that a mind suffering from dementia or aphasia will try to continue communicating however it can, in this case in a “transmodal” way, transmuting music, numbers or simply pain into painting. He also displays insight into how such a mind tries to continue thinking and figuring things out, having Ravel ask, “How many hours are in a mile? Is yellow square or round?” This seems remarkable to me – a playwright attempting to grapple with the physical nature of consciousness – and reminds me in a positive way of Jean-Claude van Itallie’s play, The Traveler, in which a theater artist felled by a stroke has to relearn how to use language.

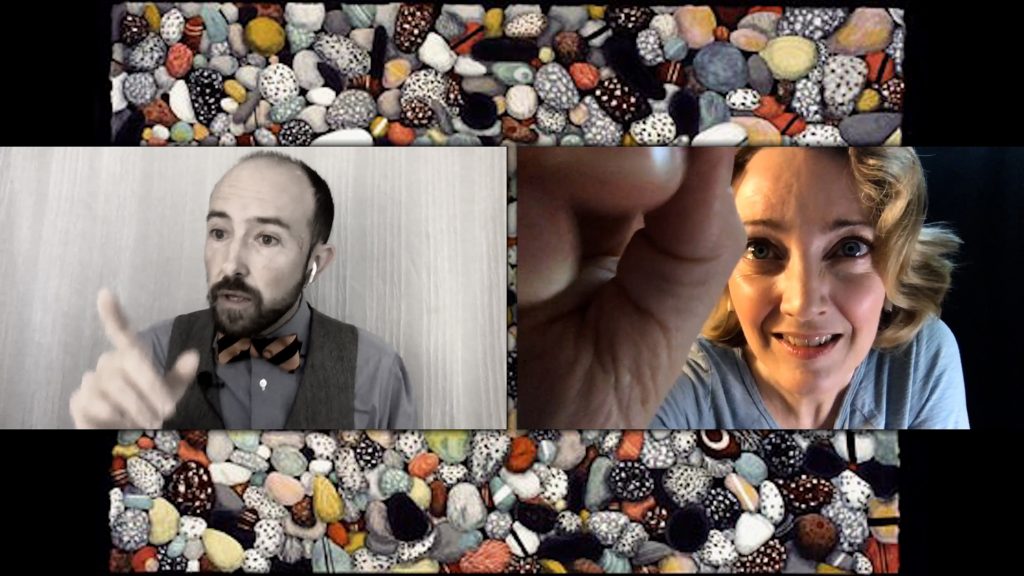

Director Nike Doukas gets fantastic performances from her cast, but equally importantly, she makes the streaming format work for her, and smartly uses this new medium to expand out the potential of the production. I don’t know if this play was written specifically for this format, but the use of Zoom-type boxes for soliloquies or for parts of a lecture are quite effective, and seeing Anne and Robert in two boxes works to create the feeling that they are close and yet so far apart. The use of a sort of desaturated color to separate the Ravel sequences from the Anne ones is a clever, subtle touch, but the most impressive artistic decision is in Doukas’ use of Anne’s paintings, in which the audience is invited to examine them deeply in a way that may not have been as possible on a traditional stage. This is especially true of the play’s inspired closing moments, in which Anne’s painting of Boléro is displayed, animated and amplified in sync with Ravel’s music, moving from left to right along the rows of the painting as if the audience is playing the piece and the painting simultaneously. It becomes a demonstration of what Anne may have experienced in the creation of this work of art, which is an extraordinary thing.

UnRavelled, presented by the Global Brain Health Institute (based at the University of California, San Francisco) and Trinity College Dublin (at the University of Dublin, Ireland), is now streaming for free on demand through March 31st by using this link.

UnRavelled is easily one of the best and most thought-provoking plays of the past year.

This is not the type of film or performance that would ordinarily interest me. I expected to be bored and didn’t think I’d “make” very long. All I can say is, “WOW!” I was captured and captivated. I loved it so much!